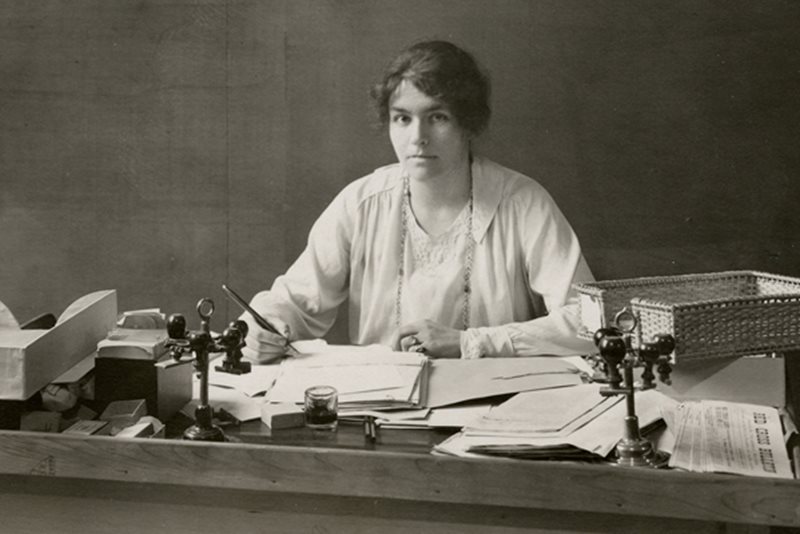

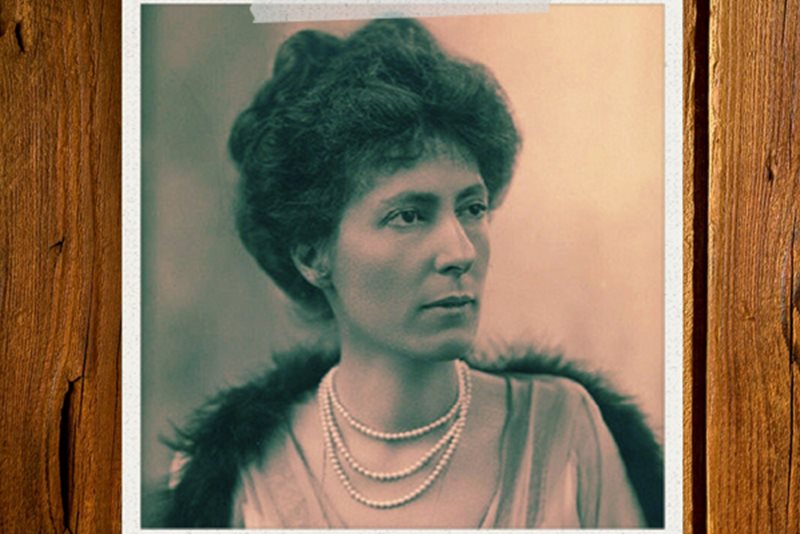

Marguerite Cramer began by studying law in Geneva and Paris. After a period working on historical research, in 1914 she was appointed professor of history at the University of Geneva. In November 1914, however, this career was cut short, during the very first semester of her professorship, when she was called on to work for the ICRC. Marguerite then followed in the footsteps of her grandfather and three of her cousins, who had previously worked for the organization, and in 1920 she cemented her ties to it by marrying an ICRC delegate.

It was not easy for women to join the ICRC at the time, and Marguerite’s appointment drew mixed reactions from her fellow Committee members. Some were worried: because she was a woman, it might set a new precedent for international organizations, and because she was from Geneva, it might rekindle old controversies about the ICRC’s mono-national recruitment policy and its exclusively Swiss Committee.

One member, Adolphe d’Espine, declared: “I object to the decision and ponder whether it is appropriate. Is Miss Cramer qualified enough to be part of the Committee like her grandfather? And is this the right moment?” Gustave Ador, the ICRC president at the time, acknowledged “the candidate’s outstanding qualities, while at the same time thinking that this appointment of a woman, the first of its kind in an international body, will cause some surprise abroad.” A forward-thinking member, Jacques-Barthélémy Micheli, was more optimistic about the decision: “I think appointing a woman would be a positive development for the ICRC, welcomed even by anti-feminists.”

Marguerite began her work with the ICRC in the early years of the First World War, when she helped get the International Prisoners of War Agency up and running. She was the ICRC’s first female diplomat, carrying out missions in Berlin, Copenhagen and Stockholm in March and April 1917 and again in December of that year. She also took part in the Franco-German conferences in Bern, organized by the ICRC at the request of the Swiss Government, which led to the repatriation of prisoners of war in 1918. She played a decisive role in the development of international conventions to protect both military and civilian victims of war and was one of the main driving forces behind the project that led to the 1929 Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War. She was also involved in drawing up a new international convention, aimed at protecting civilians of foreign nationality in enemy territory by ensuring that they would be as well treated as prisoners of war (the so-called Tokyo Draft of 1934).

During the Second World War, Marguerite devoted herself to the work of the Central Agency for Prisoners of War. She and her colleagues repeatedly tried to persuade the Committee – in particular, Presidents Max Huber and Carl I. Burckhardt – of the need for the ICRC to take vigorous action to protect civilians (hostages, deportees, forced labourers, etc.) who were being held by the Third Reich, and those interned in concentration camps. Unfortunately, these efforts were in vain. Marguerite resigned from the Committee on 3 October 1946, but the ICRC made her an honorary member – a title she held up until her death on 22 October 1963.

Globally, women hold just 24% of senior leadership positions. The U.S. lags behind the global average at 21%, compared to China where women hold 51% of senior leadership slots.